If you haven't read chapter 1, it is recommended you read it first.

A passenger named Kate Jensen, whose cabin was opposite Deeming's (then known as Williams) on the Kaiser Wilhelm ship, later wrote a letter to the Government of Victoria imploring that Deeming should not be executed due to his insanity. She claimed that on this journey he brandished a knife, claiming that he had killed many Zulu's with it and when returning to the boat in the Suez, he held up a small saw and claimed that it was a very useful implement and that he had just half-sawn off a man's hand. Jensen said he posed as a religious man but was happy to boast openly about stealing pearls off an aboriginal. He directly accused her of stealing a necklace from his wife and by the time the vessel arrived at Melbourne, many of the passengers shun him due to his various accusations against them. Jensen stated that he treated his wife with much affection and consideration and they seemed much attached. Deeming's wife spoke to Jensen about his excitable and restless nature and that he was very eager to get to Melbourne. Jensen believed at the time he was insane, and that he must have committed the murder of his new wife in a fit of insanity.

Another passenger testified at his trial that Williams appeared very pious on board and conducted several of the services himself, and always made himself conspicuous when not preaching. On one occasion he expressed horror when it was decided to hold a ball on board, and said dancing was sinful.

The newlyweds arrived in Melbourne on 15 December 1891. Deeming rented a house on Andrew Street in Windsor, a suburb of Melbourne, giving the name Mr Drewn. The owner, nearby butcher John Stamford, had been happy to rent to the man, because of his air of respectability. So impressed by him, he at first did not even know the man's name. Deeming advised them that his sister and himself had just arrived from England. Neighbours later recalled that they did not recall seeing Emily after Christmas, but her whistling 'brother' was seen behaving with “perfect sangfroid”.

On 24 December or early on 25 December 1891, he murdered his new wife and buried her under the hearthstone of one of the bedrooms, covering the body with cement. He paid a months rent in advance and left the property in early January of 1892.

He set sail for Sydney on the SS Adelaide as Barron Swanston. On the voyage, he met 20-year-old Kitty Rounsefell, who agreed to marry him on the condition he got a good job. He managed to secure a position as mine manager at Southern Cross. He sent money to her so she could join him.

One of the love letters Miss Rousefell later handed over to the police was neatly written with the faintest traces of musk. The West Australian of 25 March 1892 reported:

“It is indited from the Shamrock Hotel, Perth, where Swanston stayed for a time before his departure to the goldfields. He begins by addressing his prospective bride:—" My Loving Kitty," and goes on to tell her he is "getting along famously" in Western Australia. He assures her of his undying regard in the affectionate tones of an adolescent poet, whose passion had taken such complete possession that sleep was an impossibility and eating was altogether out of the question. He is "anxiously awaiting her arrival," and looking forward to her coming with the same old "painful longing" that most men are supposed to feel under the same critical circumstances. He is not only loving but thoughtful, and, unlike some lovers, almost generous to a fault, for he sends her some money to "go on with." The signature is that of a man who is so overcome by his feelings that writing is difficult; for the pen has staggered in the midst of a flourish, and has simulated the author's passion in copious tears of indelible ink scattered like a piece of music over the bottom of the page. Amidst it all stands out in undeniable outline the signature "Your Own Baron." There is a lot of epistolary evidence in Miss Rousefell's possession of a somewhat similar nature; but it is not necessary to do, more than indicate its bearing, as the author of the documents is not to be placed on his trial for breach of promise.”

On 3 March 1892, a prospective tenant of the Windsor house complained of "a disagreeable smell" in the second bedroom. The owner and estate agent later raised the carelessly replaced hearthstone to investigate. The smell became so overpowering "they found themselves barely able to breathe". The police were called and a body was found.

They discovered the true identity of the body after finding an invitation in the house addressed to a Mr and Mrs Albert Williams from Max Hirschfeldt. He later identified her body as that of Mrs Williams from Lancashire. They also received corroborating evidence from local tradespeople, including Stamford and his agent, a local laundress, an ironmonger who sold Deeming cement and several carriers.

A postmortem conducted on 4 March found that although her skull had been fractured by several blows, the most likely cause of death was that her throat had been cut.

Publicity surrounding the gruesome finding of Mather's body was considerable. Within a few days, The Age newspaper had connected the murder to the Whitechapel Murders.

Police now also had a very good description of Mr Williams, which they circulated to other Australian colonies, but at this stage, his real identity was still unknown.

At an inquest held on 8 March, it was discovered that a man answering Mr Williams' description had auctioned a variety of household goods, possibly wedding presents, for 60 pounds in early January 1892. At this time he was staying at the Cathedral Hotel in Swanston Street, Melbourne, registered as Mr Duncan. It later transpired that Deeming had also written an affectionate letter (as Albert Williams) to Mather's mother several days after Mather's murder.

Deeming also found time to approach Holt's Matrimonial Agency (as Duncan), wishing to meet a young lady with matrimonial intentions. He had also found time to swindle a local Melbourne jeweller.

Mrs Shelby of Riley Street, Woolloomooloo, thought the description of Williams resembled a Fred Deeming who had recently visited her after an absence of 10 years. She had previously been his landlady during his first visit to Sydney. Deeming's true identity was finally established.

A portrait of Williams, published by the Newspaper Argus, led to a lady resident of Hamilton claiming it had a likeness to Deeming's brother. The report stated that the lady, who at one time lived at Birkenhead, England, said that:

“Frederick Deeming's wife arrived at Birkenhead about Christmas, 1887. A few weeks afterwards she was joined there by her husband, who, being very flush of cash, treated all his relatives to jewellery. He took a large house in Bridge-street and furnished it in a most elaborate fashion. He invited his brother Albert and his wife to live there. Mrs Fred Deeming and Mrs Albert Deeming were sisters. Shortly afterwards Mrs Fred Deeming had a child, and her husband left for Africa, it was supposed. Time passed on, and Mrs Fred Deeming left Birkenhead to rejoin her husband. She was never afterwards heard of. She claimed there were three brothers, Fred. Albert, and Walter Deeming. They lived in partnership at Birkenhead as plumbers and gas-fitters and they dissolved their partnership around 11 years prior. While Albert and Walter went to work in Laird's yards, Fred emigrated to New South Wales. The lady said Deeming always talked big, and she was satisfied that Williams was Deeming.”

As there is no proof Deeming ever went to South Africa, it may have been a story he often told to explain his new-found wealth. It also provided him with many entertaining stories of killing multiple lions and Zulus.

Police in Melbourne traced “Williams” to the SS Adelaide where he becomes “Swanston”. Sydney detectives then pointed the Melbourne Police to Southern Cross.

Fortunately, in March 1892, Constable “Taffy” Williams from Western Australia arrested Deeming. At the time he was carrying a dagger, five pocketknives, four razors, an axe and a black cloak.

When his fiancee, Miss Rounsefell read of her lucky escape in a Melbourne newspaper, she reportedly fainted in the street.

Deeming was charged as Williams. As it was then pre-Federation, an extradition order was needed to send him to Melbourne. Detective Cawsey and Max Hirschfeldt travelled from Victoria to identify 'Williams' and extradition was granted.

On the way back to Melbourne, threats of lynching were made at every town. Interest in the case was high and there were numerous newspaper reports about him as he provided the papers incredible stories to publish.

The New York Times reported in April 1892, “Deeming has confessed to his lawyer and doctors who examined him that he committed the majority of Jack the Ripper crimes in the Whitechapel district of London.”

It was also reported that he confessed to the murder of his wife to the chaplain of the jail, Rev. H F Scott. The report was as follows:

“He says that altogether he made four attempts upon his wife's life. The first took place in London shortly after their marriage. At 2 am, he says, he was awakened by the nightly visitation of his mother, who commanded him to kill his wife. For a time he resisted her promptings, but at length, the impulse became so strong that he crept quietly out of the bed and seized a chair with the intention of dashing out his wife's brains. As he raised the chair she woke up, and, surmising his intention, jumped over to the other side of the bed, just in time to save being struck by the chair, which fell on the mattress, and was splintered to atoms. This attack he managed by some means to explain away, and the couple lived happily together until their arrival in Melbourne. Then while they were staying at the Federal Coffee Palace he was moved once more to murder his wife, and the impulse grew so strong that he woke her up and implored her for God's sake to leave him and go away, or else he would murder her. He says that she threw her arms round his neck, and told him that she would rather die than leave him. The attack on this occasion lasted only for about half-an-hour. On December 18 they took the house in Andrew Street, Windsor, and stopped there on the nights of the 18th, 19th, and 20th, sleeping on the hair mattress, to which frequent reference has been made during the progress of the case, and which now remains in the possession of a storekeeper at Southern Cross, West Australia. On the night of the 19th, he says, yielding to the same murderous impulse, he attempted to cut her throat, and her life was only saved by her sudden awakening. But on the following night — that of December 20, he woke once more at 2 am and found a candle, which rested on a trunk beside the bed lighted, and his wife sitting up in bed peeling an apple with a large clasp knife. He wrenched the knife from her hand, and cut her throat. When the murder had been done, he was seized with an uncontrollable fear of the dead body, and without daring to look at the dead woman, he rushed out of the house, leaving the body where it had fallen among the coverings. As day broke he found himself on the St Kilda Pier, and there he saw a man fishing. The man's appearance was wretched and poverty-stricken, and after studying him closely for a while, the prisoner says that he spoke to him, and asked him whether he wanted a job. The strange man replied that he would do anything short of murder for £5. Williams then, according to his own story, asked him whether he would undertake to bury the body of a dead woman, and the man replied that be would not do it for £5, but that for ten he was ready to do anything. Williams gave him £2 as an advance, and taking him to the house in Andrew street, unlocked the door and let the man in. That night he slept at the Cathedral Hotel. On the following day, he met the man by appointment, gave him the balance of £8 and went away, after assuring himself that the house was properly locked up and that from the outside at least there was not any sign of disturbance. Of how the body was put out of sight the prisoner declares that he knew nothing and that until the first news of the discovery reached him in Western Australia he did not know that it had been buried in the cement beneath the hearthstone. On this narrative, Mr Scott put several questions to the prisoner. He asked him first how it was if the murder had been committed during an uncontrollable impulse, that the cement and the necessary tools for the burial had been purchased beforehand. The prisoner replied that it was so, that the evidence of the witness Woods, which he had so strongly criticised in court, was perfectly true, but that he could not account for it, because, 'Sometimes he was not himself.' He described the knife with which the murder was committed, and said that it would be found among the contents of the large trunk which was sent down from Southern Cross after his arrest. Mr Scott accordingly visited Detective Cawsey, and a knife, exactly answering the description, was found as the prisoner had declared. Additional proof was afforded by the fact that one of the medical men concerned in the case, who was completely unaware either of the prisoner's statements or of the existence of the knife, gave Mr Scott a description of the weapon by which the wounds in the throat might have been caused, and this description applies exactly to the knife found in Deeming's trunk. It was also pointed out by Mr Scott that this story of the murder contained no reference to the wounds in the head. Deeming, after some consideration, replied that he could not account for these injuries and that he knew of no weapon by which they could have been inflicted. On the subject of the Rainhill tragedy, he also spoke freely, repeating with some variation of detail the account of the murder by 'Old Ben' and Emily Mather given in the medical evidence at the trial. The prisoner was privately visited yesterday by Miss Rounsefell, sister of Miss Kate Rounsefell. To her he handed a sketch of two tombstones, supposed to have been taken in a South African cemetery, between which, he said, a sum of £11,000 in gold had been buried. The interview in other respects was of a private nature. After Miss Rounsefell had gone, Deeming showed himself subdued and quiet and occupied some time in writing verses of a more or less melancholy character. In the evening he was visited by Mr Shegog, the governor of the gaol, who informed him of the decision of the Executive. 'I have bad news for you,' said the governor, as he began his statements. 'Bad news!' replied the prisoner, when he had heard the end; 'I think it is good news. The best news you could possibly have told me.' It may be seen later whether the failure of his last hope will produce any marked change in the convict's demeanour.”

The following was reported in the West Australian, 18 March 1892:

“The people who met Swanston in Perth or Fremantle are very numerous if all the accounts that one hears are to be relied on, and it would certainly appear that he was very far from endeavouring to elude observation. The most remarkable rumour is that he was seen in Perth in company with a stylishly-dressed woman. This is a rumour which certainly deserves investigation, as it yet remains to be seen whether it rests on a solid basis. What, however, may prove a clue of considerable value is that some photographs said to have belonged to Williams have been handed over to the police. One of these is of a cabinet size and represents a young woman fashionably dressed, but with a figure inclined to embon-point. Of course, people who jump at conclusions are at once ready to assume that the photograph represents Mrs Williams, the victim of the Windsor tragedy, and should this prove to be the case, the value of the clue does not require labouring. That, however, is one of the many points which yet remain to be proved. Other photographs are also said to have been found. One of these is of a young woman, another of a lad, and another of an infant. It is a fact worthy of notice that on the photograph of the woman supposed to be the Windsor victim, the imprint appears to have been carefully removed. The other photographs according to the imprint on their backs, were taken at Sheffield, Whitehaven, Liverpool, Ohio, Sydney, and Rockhampton. It is possible also that some clue may be gained from Swanston's hats, which have come into the possession of the police, and if so it will not be the first time that a hat has played an important part in a murder trial. The fact, however, that Swanston possessed a " bell-topper" and two soft hats such as Williams is said to have worn in Melbourne, cannot in the absence of further information afford very much room for surmise. Another statement more difficult to believe is that while at Southern Cross, Swanston gave away pieces of music, on which the name, Albert Williams, can be deciphered in the corner. Supposing that Swanston is Williams, this seems almost incredible rashness on the part of one who has apparently displayed so much care and ingenuity in destroying all trace of his crimes. Swanston arrived at York yesterday afternoon under police escort and will be brought down from York by train today. It is understood that the party will travel by train reaching Perth Station at 1.50 this afternoon. The accused will be brought up at the City Police Court on Saturday morning and remanded, pending the arrival of Detective Cawsey and Mr Max Hirschfeldt, a fellow passenger of Williams and his wife on the journey from England.”

This account of him from a person from Southern Cross in November 1900, seems to be an honest account of his impression of him:

“There is a certain amount of misunderstanding regarding "Deeming," or as he was known here, "Baron Swanston." His cards bore the name Baron Swanston. Now, he is generally supposed to have been a cruel and fierce-looking brute, with a sort of Bill Sykes face. As a matter of fact, he was nothing of the sort. Swanston was a little man, slight, with a whitish-yellow moustache, square shoulders, with a slight suspicion of a stoop, very neat and natty —in fact dapper - a very nice man to speak to, pleasant and chatty, conceited, and generally nice looking. He made himself very pleasant at the Exchange Hotel, where he boarded, and everyone liked him very much, though afterwards they all "suspected him of being a murderer from the very first." He lived in a house on Frazer's lease, which is still standing, and I saw the cement floor being put down. One day I was talking to the manager of the mine, who lived in the same place (Deeming's house). I was about to leave when Deeming (or Swanston as we knew him) came into the room and said to us, "My little girl is coming over in the Oceana, have just had a wire." He showed us a telegram and we congratulated him and made some pleasant remarks. He left, and soon after I left also. An hour later I saw him pass by "with gyves upon his wrists." He had in his possession music with the name " Williams" imperfectly rubbed out and quite readable. He also had a small battle-axe half the size of a hatchet and a lot of neat and ingenious articles. He told the most exaggerated stories of killing lions and panthers in Africa, and of a terrific combat with a giant Zulu, whom he slew with great difficulty. He joined in the musical evenings at the hotel with great pleasure, though I don't remember that he sang or played. It is said that he had a light burning in his room all night. He got drunk only once and seemed much annoyed the next morning and never repeated the experiment. I may mention that it was hard not to get drunk every day in those times. His arrest caused great excitement here and the Court was crowded. He was one of the most celebrated of all murderers and everyone has heard of his subsequent deportation and execution.”

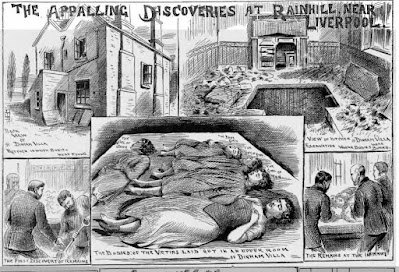

Following the publicity surrounding the discovery of Mather's body at Windsor, investigations at Rainhill revealed the decomposing bodies of Marie Deeming and the four children; Bertha (aged 10), Maria (7), Sidney (5) and Leala (18 months) buried beneath the re-concreted floor of Dinham Villa.

The throats of all of them except Bertha had been cut, Bertha had been strangled. Maria was lying face downward on the left side of her mother, the baby was lying face downward on the mother, Bertha was at the foot of her mother on her right side.

The murder and burials had occurred while Deeming was courting Mather, on or about 26 July 1891. At an inquest held at Rainhill on 18 March 1892, Deeming's brothers identified Marie and gave some accounts of his activities.

The Rainhill murders had gone undetected for eight months. It appears Deeming's brothers and Marie's sister had been led to believe that Marie and the children were in Brighton on a holiday and then assumed they were overseas again. Deeming had made several visits to Birkenhead to reassure Martha that her sister and the children were well. Detection of the murders was also obstructed by Deeming's lease (as Williams) on Dinham Villa, which stipulated that the house should not be sold or relet for six months, because of the imminent arrival of Colonel Brookes and/or his sister.

Deeming was defended by Mr Alfred Deakin (who later became Prime Minister). The only defence Deakin mounted was that of insanity and the public pre-judging of his client.

The following was reported on the 25 May 1892:

“DEEMING'S EXECUTION. On Monday morning, at 10 o'clock, the scoundrel of the period, Frederick B. Deeming, alias Williams, suffered the extreme penalty of the law, in Melbourne Gaol, for the murder of his wife, nee Emily Lydia Mather. The prisoner slept soundly on Sunday night and had to be woken up by the Sheriff at seven o'clock in the morning to have the irons removed. At 10 a.m. Sheriff presented the execution warrant to the Governor of the gaol and demanded the body of "Albert Williams." The convict was then brought out, pinioned, and placed on the drop. When asked if he had anything to say, "Because now is the time to say it," the prisoner's only reply was, "Lord receive my spirit." He stood firmly on the drop. Death was instantaneous. A large crowd assembled outside the gaol and received the news of the execution with brutal cheers.”

Death seemed to follow Deeming, so it is not surprising to read of another lucky escape in Southern Cross. The following was published by “Dryblower” on the 18 March 1934 in the Sunday Times (Perth). “Dryblower” was a regular contributor to newspapers regarding the early days in the Goldfields. He was a good story-teller, so there is probably little truth in it. As you will soon read, the rescued man who is at the heart of the following story, died in Coolgardie in this story, but he retired in New Zealand in another story published by Dryblower 10 years prior! I'll repeat it anyway, as it is quite poetic and is what led me to learn of Deeming in the first place.

“The recent recovery of an old empty coffin from an abandoned shaft at Southern Cross supplies the last link in the narrative of an uncommitted murder.The main items in this hitherto unpublished narrative of how a one-time well-known mining man was close to being done to death by Frederick Bayley Deeming have been known to the writer for many years— forty-one, to be exact. The finding of the old "wooden overcoat" near the scene of Deeming's arrest early in 1892 completes the proof of the failure of a crime so diabolical that criminal history has no parallel.It will be no news to the middle-aged and elderly to be re-informed regarding the arrest in Southern Cross of the then called "Assassin of the Century," Deeming, the man who killed and buried in cement beneath the hearthstone at 67 Andrew Street, Windsor, Victoria, Emily Mather, a young and pretty girl whom he lured to her death after killing his wife and four children at Rainhill, in the North of England.These were found also brutally murdered and embedded in cement in the cottage where he had lived at the said town of Rainhill, the finding of the five bodies being a sequel to the discovery of Emily Mather at Windsor, Victoria.With those murders, horrible as they were and international in their interest, as many others were considered to have been done to death by him, this narrative has little to do, except to illustrate the ferocity and fearfulness of Deeming, and the lengths to which he assuredly would have gone to ensure more victims and the money that might have been his had the Southern Cross plot gone on to fruition.Let us go back nearly 41 years to the early part of 1893.The writer was one of a party of swampers tramping to Coolgardie in the middle of that year.Halfway across the Boorabin sandplain, an old man was rescued from death by thirst and exposure by the hearing of the playing of a piano, carried on a wagon, a campfire concert being held nightly.The old man had wandered away into the bush north of the track, had become bushed, and had given up hope when he heard the sound of a piano and a score of voices lustily singing the chorus of "The Man That Broke the Bank of Monte Carlo."The story has been told before, but for romantic realism and vivid interest, it has never been excelled.That chorus saved the old man from absolute death, and he was whole-heartedly grateful to his accidental saviours, the writer amongst them.Less than a year later he died nameless in the rough bush hospital at Coolgardie. Before his poor, tired soul passed over into the Valley of Shadows he told the writer a remarkable story, the coffin but recently found at Southern Cross being one of the central items in his narrative.Many times he stopped in his story, and many times he needed stimulant to enable him to proceed. Where he had originally come from he told no one, nor was his name known. There had been a dark page in his previous life that had probably been known to Deeming, as, whenever the name of that monster was mentioned, the now passing out veteran shuddered. Sometimes, the nurses said, he spoke as if he thought Deeming was still alive and could do him harm, all their assurances being unavailing to soothe him.This was his story to me as he lay hovering between this world of light and laughter and the problem paths of the next.He had been employed as a handy and general utility man on the same mine as Deeming; the latter was engine-driver.Deeming inhabited the old mud-walled hut shown in our illustration, the old man sharing a corner of it.It had originally been the Southern Cross lockup, some of the old prison bars still remaining in the small windows.One morning, after the old man (whom we shall call X), had been drinking heavily (he had some secret of his own, the nature of which he refused to divulge). Deeming threw a bucket of water over him to bring him to his senses.Then he told the old man that he (X) had been babbling all night about a crime he had evidently committed, but for which he had paid no prison penalty. (Neither I nor the nurse urged him on that point.)Terrified as to what Deeming really knew of his past, X grew as a timid dog under the hideous whip of a cruel master. All Deeming demanded of him he did, not willingly, but in fear.One night he returned to the hut unexpectedly and found Deeming making a coffin inside the old room he used as a sleeping place. As he turned away in terror he stumbled and was instantly dragged into the house. A heavy blow knocked him senseless, and when he recovered the coffin was gone and Deeming was apparently sound asleep.Next day when he knew positively that the man he feared was several miles away selecting timber for mining work, X searched around, and, discovering a newly-disturbed part in the floor, scratched until he found the entrance to a shallow cellar. Descending the steps, he found it to be an old cooler used in the police days to hold perishables.The newly-built coffin was there and seemed made to hold a very big and bulky man or woman, presumably a man.Not letting Deeming know of his gruesome discovery, he went about his work as usual.Next week Corporal Williams, now farming near Pingelly, with the aid of the mine manager, Captain Oats and three burly miners, got the handcuffs upon Frederick Bayley Deeming for the murder of Emily Mather at 57 Andrew Street, Windsor, Victoria.The day before Deeming was taken away heavily guarded, in the coach running from Southern Cross to York, and thence by train to Perth, a half-caste native, who had been employed to take Deeming's meals, etc., into him, brought a rough scribble to the mud hut where Deeming and X had lived."Find and burn what you saw me making," ran the pencilled note, "or I'll split to the police what I heard you talking about in your sleep."The old man paused in his broken but vividly interesting narrative as if expecting to be asked the nature of the crime or misdemeanour he had committed, but he was, naturally, not worried."Did you ever find out for what purpose the coffin was made?" he was asked."I found nothing about it," said X, "excepting that, in searching around, I found a page cut from an old detective magazine where a South African mine manager had been secretly poisoned, and after he had been screwed down in his coffin a lot of gold had been put in around his body. The grave was afterwards opened by his murderers, and the stolen gold removed. I have often thought," continued the old man, "that something like that was in Deeming's mind. I sent a note back to him to say I'd do his bidding, and he smiled and nodded to me as they took him away on the coach. "When I knew he was safely hanged, I took the coffin out one dark night, and threw it down a shaft."

Now for those interested in the history of the first piano in Southern Cross and then Coolgardie, I return to Norma King's article that sent me down the Deeming rabbit-hole.

Norma's account was based on Dryblower's publications. He stated that Deeming charmed his listeners with his skill on the piano and that his “prowess as a pianist” in Southern Cross had helped police trace him. However, this statement cannot be substantiated. There is no mention of it in the published police records in Covell's book, or in any of the newspaper articles I have read. Indeed, the writer of the account previously quoted did not remember him singing or playing the piano.

“Dryblower's” story relating to the piano helping the lost man, may have a grain of truth in it. However, he publishes two other versions of the story, and they don't state that he died in Coolgardie in Dryblower's presence!

Like the version above, in one version published prior, he states that in August 1893 a 'swampers' wagon was carting the piano from Southern Cross to Coolgardie. Each night the men camped near the wagon and someone would play it on the wagon while they stood around it and sang. One evening at about nine o'clock on the Boorabin sand-plain, a 'half-naked elderly man, gasping and gibbering in a most piteous manner, crawled on his hands and knees into the light of the camp-fire and motioned thirstily for water.' The next day he was able to tell them his story. He and his mate had been among a party travelling with a team two days ahead of the wagon carrying the piano. He had wandered off the track and had not been able to find his way back. His mate, who classed himself as an expert bushman, did not stay behind to search for him but went on with the others. The lost man said that just when he was almost delirious from thirst and fatigue he heard the tinkling of a piano in the wilderness and made towards the sound.

When the man and his rescuers reached Coolgardie, they went straight to the little tent hospital where the old man stayed under the care of the nurses. The others searched for his ex-mate. When they found him, they gave him a 'good belting' and sent him on his way back to where he came from.

Another version he gave 10 years before the above version is as follows. With the wagon were himself, a few musical mates, including Billy Hansen and an older New Zealand prospector known as “Maori”. Maori wandered off to inspect some promising quartz and did not return. The next day the team moved to the Boorabin sand-plain. They discussed what may have happened to the old man and a driver said he found his swag and that his mates were still among the team. They searched for the man, but his mates said that he had often talked of going back to Southern Cross. As many teams travelled on a nearby track, they assumed he got a lift with one of them. That night during their concert, poor old Maori was heard calling out near their camp. He found them by following the sound of their singing with the piano. They left him to recover at Snell's old Shanty tavern at Boorabin Rock. When he recovered, he returned to Southern Cross after being given a few ounces of gold from the locals. Dryblower then claimed that Maori's ex-mates were tried before a 'roll-up' judge and jury and were given 24 hours to leave the field by 'coach, team, boot or wheelbarrow'. They were fined 2/3rds of their cash and were forced to sell all of their supplies and tools. They sent the proceeds to “Maori”, who was then at the public hospital in Perth. With the proceeds, he returned to New Zealand. In this version, he didn't die relating the story of his lucky escape from Deeming's murderous rampage! It seems as though the tale gets more colourful as time progresses.

The piano on the wagon did exist and was most likely delivered to Faahan's Club Hotel in Coolgardie as Arthur Reid claimed in his book “Those Were the Days”. Dryblower's early account verifies this fact also.

Faahan's hotel was the gathering place for the “Bohemians”. Some of the men who gathered around the piano were quite talented, and one, Albert Waxman, under the name of Albert Werean, later went to London and became a big attraction in the music halls.

Other singers were Ben Strange, Billy Hansen and Sam Bennett. The last two were known locally as 'the musical twins' and were much in demand at social functions.

By 1900 the piano had become so well used that Faahan sold it and replaced it with a new one. The buyer of the old piano purchased a part of the early history of the Eastern Goldfields and it was the centrepiece of a couple of good yarns, no doubt told around the campfires at the time. It was even reported that the story became part of Edward Forde's lecture tour of England, further extending the reach of the colourful story.

Sources:

“Frederick Bailey Deeming: 'Jack the Ripper' or something worse?”, Covell, M, Creativa, 24 September 2014

"Deeming” (Contributed) The Southern Cross Times, 3 November 1900, p3 https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/206584631

“A Few Goldfields Firsts: A Chronicle of Early Coolgardie-Policemen, Pianos, Parsons and Passouts” Dryblower, The Sunday Times (Perth), 9 May 1920 p1, https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/57965855

“Did Jack the Ripper roam the streets of L.A.?” Bartlett, J: LA Weekly, https://www.laweekly.com/did-jack-the-ripper-roam-the-streets-of-l-a/ 24 May 2017.

"Don't Marry in Haste” Dead and Buried, Episode 1, Season 2, Godden, C & Hooper L, http://www.deadandburiedpodcast.com/dont-marry-in-haste, 24 February 2019.

“Jack the Ripper Suspects: Was killer Frederick Deeming hanged in Australia? McNab, D: 7News.com.au, 7 November 2019,https://7news.com.au/original-fyi/crime-story-investigator/jack-the-ripper-suspects-was-killer-frederick-deeming-hanged-in-australia-c-490935

“The Windsor Murder: Deeming sentenced to Death” Lilydale Express, 6 May 1892 p3, https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/252177692

“The Historic Piano of the Demon – Deeming, Saves a Man's Life” Truth (Brisbane) 7 April 1901 p2, https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/200507169

“The Windsor Murder – Deeming's Confession” Wagga Wagga Express, 12 May 1892 p3, https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/145529905

“Piano and Violin” Sunday Times (Perth) 16 February 1930 p1, https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/58375505

“The Windsor Murder. Startling Developments” The West Australian (Perth) 18 March 1892, p3, https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/3033292

“The Mystery of Deeming's Coffin: The story of a contemplated murderer” Dryblower, The Sunday Times (Perth) 18 March 1934 p10, https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/58716477

“Deeming and the Whitechapel Murders” Inquirer and Commercial News (Perth, WA: 1855 - 1901), Saturday 28 May 1892, page 3 ) (https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/174511191)

“Another Letter from Swanston to Miss Rounsfell” West Australian (Perth), Friday 25 March 1892, page 5, https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/3033628

Queanbeyan Age (NSW: 1867 - 1904), Wednesday 25 May 1892, page 2

No comments:

Post a Comment